You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Children’s Books’ category.

This is the fourth in a series of posts about the 2008 Rutgers University Council on Children’s Literature One-on-One Mentoring Conference. Click on the RUCCL tag above to read them all.

Vivian Grey, accomplished author and founder of the RUCCL conference welcomed attendees to an “extraordinary creative collaboration.” Why did she use those three words? The RUCCL is unlike any writing conference of its kind, matching new and aspiring authors with experienced professionals for an in-depth discussion of children’s literature—on whatever topic the mentee wishes to explore.

“Use this day to move your writing career forward,” Ms. Grey said. “The RUCCL pioneered and developed the one-on-one format and helped launch the careers of many well-known authors: Marcie Aboff, Laurie Halse Anderson, Denise Lang, Pamela Curtis Swallow, Kay Winters, and Rita Williams-Garcia.” (And I’m sure I didn’t catch them all!)

When Vivian Grey approached legendary Rutgers President Mason Gross in 1970, he enthusiastically supported her idea and assured the conference a permanent home at Rutgers through a presidential charter. The RUCCL is the only group in the country to be recognized in this manner. Aspiring authors can be confident knowing that this organization will continue to inspire us year after year.

Ms. Grey left us with words of wisdom based upon our difficult times. “We live in an era of great confusion and agitation,” she said, referring to the upcoming election, our suffering economy, and the wars raging overseas. “Children are vulnerable and powerless. But we can listen to them and be their voice. We can help them understand this increasingly confusing world.”

She continued, “There’s no better time than now to be writing for children. The vision we create for children becomes their future.”

Bravo, Vivian. The vision you created for us will indeed become our future, too.

This is the third in a series of posts about the 2008 Rutgers University Council on Children’s Literature One-on-One Mentoring Conference. Click on the RUCCL tag above to read them all.

Author Kay Winters is a RUCCL success story. Who better to give the introductory speech? She attended the one-on-one conference three times before she was published, but now has 14 books in print with 5 more under contract. She came to inspire. And she did with this simple yet powerful statement: “I’m here to tell you: it can be done.”

Ms. Winters spoke of her journey to becoming an author, which began in childhood with a love of books. She always wanted to be a teacher, however, and that is what she became. But she still wrote for pleasure, penning articles, short stories and poems that never made much money. Writing to make a living didn’t seem possible.

Ms. Winters spoke of her journey to becoming an author, which began in childhood with a love of books. She always wanted to be a teacher, however, and that is what she became. But she still wrote for pleasure, penning articles, short stories and poems that never made much money. Writing to make a living didn’t seem possible.

She eventually co-authored a book about teaching. But the long hours writing plus being a teacher created a tiring pace that she could not sustain. When a local author visited her school, he told her, “Give yourself five years to break into the business.” She thought, “I need to get going!” Shortly thereafter, her school offered an early retirement package. Her letter of resignation was on the Principal’s desk the next day. She wanted to write full time.

“When I quit teaching, I worried that I would miss the hugging,” Kay said, referring to her students. “But children’s writers are hugging.” We all laughed. We know. She was already hugging us.

After her retirement, Kay took classes at The New School and spent afternoons at the Children’s Book Council reading every single picture book that they received. Thousands of them. She joined two writers groups. She subbed her manuscripts. Wolf Watch was rejected 17 times.

But she came to RUCCL with hope and left inspired. The encouragement she received at the event kept her spirits up despite the rejections. “I think I can” became “I know I can!”

And on her third trip to Rutgers, Kay’s agent-mentor took a look at her picture book manuscript and said, “This is publishable.” And then another. “This is publishable.” She left fired up!

It was soon thereafter that the offers came pouring in. They say good things come in threes. This was true for Kay, who sold Teeny Tiny Ghost to HarperCollins, and the oft-rejected Wolf Watch was snatched up by Simon & Schuster just two weeks later. Viking then offered a contract for Did You See What I Saw? Poems About School.

Kay now spends her time writing, speaking at conferences and making school visits. She especially loves hearing from her student-fans:

Dear Ms. Winters, thanks for coming to our school. Your assembly was awesome. I wasn’t there.

and another charming young man asked:

How old are you? Were you on the Titanic?

OK, she doesn’t have as much experience as that child thought, but she has been in this business long enough to impart three very important tips for all aspiring writers.

- Word Hard.

- Let your manuscript breathe. Don’t send it right out. Give it some time and revise.

- Have persistence. Because there is a lot of talent out there, but persistence is in shorter supply.

Kay ended with something a mentor once told her: “I’ve never known anyone who wanted to do this, who worked really hard, and didn’t succeed.”

Thunderous applause for Kay Winters! She gave us her own magical story.

Rules, Tara? Why are you writing about rules? K.L. Going just urged writers to shake off the rules and “step boldly across the lines.” We are creative souls! We don’t want more restrictions!

Ah, you are right. But remember, Ms. Going also said that writers need to be educated. Know those rules and understand why they are in place. Only then can you decide where to successfully break them. Then you don’t have to call them rules anymore—think of them more as suggestions.

Yesterday I met with Alyssa Eisner Henkin of Trident Media Group, an experienced professional who came to agenting via the editorial track. She knows this business. She knows what sells. So when she gave me five rules for picture books, I took careful notes.

Rule #1: Audience age is 2-6 years old

This one was a little surprising to me. I often see PBs categorized in three ways: baby board books, toddler books, and books for 4-8 year olds. But eight year-olds are not reading picture books. They may be classified that way for teachers who want to read aloud to their class. Unless you’re writing board books, think of your audience as 2-6 years of age. What situations will they relate to?

Rule #2: 500 Words is the Magic Number

Again, another suprise–somewhat. Yes, I’ve heard about that 500-word mark, but I’ve also heard about the 1000-word barrier. Most of the books I read my own children are closer to 1000 and sometimes more. Personally, I don’t often spend $16.99 on a 500-word three-minute experience. My children and I enjoy sharing stories at bedtime and a short one can sometimes leave us feeling short-changed. Ms. Henkin said she’s heard the same thing from many parents, so I asked, “Why is there this disconnect between parents and the industry?” It’s all about perception. The current industry perception is that today’s parents are busier than ever and they want short books to put their children to sleep quickly. OK, that’s not true in my house, but I’m a statistic of one. Publishers are buying 500 words or less. Repeat after me: 500 or less.

Rule #3: Make it Really Sweet or Really Funny

Maybe this isn’t so much a rule as a great suggestion. These kind of books are easier to sell. People get it. Elevate your “awww” factor. Make the laughs side-splitting.

Rule #4: Use Playful, Unique Language

When publishers say they seek a “unique voice” that doesn’t only apply to middle grade and young adult novels. The sounds words make are new and interesting to young children. Play it up.

Rule #5: Create Situations that Inspire Cool Illustrations

PB writers are told to leave enough unwritten so illustrators can tell half the tale. But that’s not enough to be thinking about. Go a step beyond. What story situation will inspire an unusual, unique illustration? Something you’ve never seen before? Don’t just leave room for pictures, leave room for AWESOME pictures. The cooler the art, the better the book.

Another thing that I brought home with me after our PB discussion was concept. Many times, I’ll get a spark of an idea and immediately sit down to write. I will start taking more time to develop that concept, thinking about all the rules above before ever putting pen to paper (or fingertips to keyboard). And then maybe I’ll decide to step over one or two of those lines. I’m a creative soul, after all.

This is the first in a series of posts on the 2008 Rutgers University Council on Children’s Literature One-on-One Mentoring Conference. (Because I have 20 pages of notes to share!)

Phew! What a whirlwind day! I mingled with editors, mixed with agents, and milled about with other aspiring authors at the RUCCL mentoring conference. My head is spinning with suggestions. So where to start? Well, I’ll begin at the end, with keynote speaker K.L. Going. The author of Fat Kid Rules the World and The Liberation of Gabriel King wrapped up the event with an inspiring speech about “writing across the lines.”

Agent Linda Pratt introduces K.L. Going

K.L. began by telling us what we already know: as writers, we have many, many rules to follow. Manuscript length. Formatting. Submission guidelines. Avoid passive voice. Don’t write didactic tales.

“But writers are creative souls,” she said. “It’s hard for us to color within the lines.”

She stopped her speech and asked everyone to stand up. And then she told us to shake off those rules! So I grabbed my friend Jill by the shoulders and shimmied her around. She returned the favor. Wubba wubba wubba! Boy, that felt good!

“Despite what anyone else says,” she said, “there are times you must step across those lines.” She relayed her early writing experience, sitting on the floor of her sparse employee housing at Mohonk Mountain House, typing away on her laptop. It was the happiest time in her life because she wrote without rules. She didn’t care if anyone read her work, she simply wrote because that’s what brought her the most joy. She wasn’t thinking about marketability, high-concept hooks, or the current list of best-sellers. However, it was also the least productive time in her life since she wasn’t writing with that intention to sell.

So how can writers be both happy and productive? You need to choose which lines you’re willing to cross while staying inside others. With Fat Kid Rules the World, she wanted to create a character that wasn’t familiar. Troy is dirty, smelly and raw. And to some, offensive. That was a line she was willing to cross, potentially alienating some readers. But, she still wanted Troy to be lovable by the end of the book. She could not compromise on that essential rule of writing: creating likeable characters.

“You need to write what you want regardless of whether you think anyone else ‘gets it’,” she said. “But writing what you desire is always a risk.” With Fat Kid, she didn’t necessarily cater to the reader. There’s a hunk of bleeding leg and splattering of fat when Troy envisions the results of his own suicide, and some people may put the book down at that point. (In fact, her book was banned in some areas.) But others will stick with it and read on. If the reader’s journey isn’t easy, maybe it will be more redemptive and satisfying by the end.

“You need to write what you want regardless of whether you think anyone else ‘gets it’,” she said. “But writing what you desire is always a risk.” With Fat Kid, she didn’t necessarily cater to the reader. There’s a hunk of bleeding leg and splattering of fat when Troy envisions the results of his own suicide, and some people may put the book down at that point. (In fact, her book was banned in some areas.) But others will stick with it and read on. If the reader’s journey isn’t easy, maybe it will be more redemptive and satisfying by the end.

She cautioned us further: you need to balance your risks. Troy may be unusual, but his emotional struggles are immediately known in the first chapter. Readers may not relate to his appearance, but they can relate to the critical inner voice we’ve all had whispering in our ears at some time in our lives.

K.L. told us it’s important to know the rules. Because you can only make educated decisions about your manuscript when you have knowledge of the industry. “But don’t forget that creativity has its own demands. Don’t be afraid to try something different. Step boldly across the lines!”

So, where are the lines for you?

Last week Nathan Bransford asked blog readers to tell him about the worst piece of writing advice they ever received. I didn’t participate because I couldn’t think of anything. Sure, there was the critique partner who rewrote my manuscript in her own style. Yeah, I’ve been told a story was ready for submission only to realize, months later, that it needed more work. And a writing professor once banned the entire class from killing off characters. He didn’t want us to come to a rough patch in our story and take the easy way out. I didn’t agree with the rule, but it was understandable.

I don’t consider any of that bad advice. Poor judgment, maybe, but not faulty guidance (especially since I didn’t follow it).

The best advice is not really advice at all, but when a publishing professional relates his or her own experience to an aspiring author. Advice is subjective; it’s based upon personal circumstances. If you don’t know the story behind the advice, then it’s impossible to gauge whether or not that advice will work for you.

So don’t give advice. Tell others what you’ve learned and how you’ve learned it. Share your experience.

The children’s writing world is filled with many generous professionals who volunteer their time to assist those of us starting out. Never before have I met such a kind and welcoming group of people. I have to say that no one has given me a bad piece of advice yet. And hopefully I won’t steer you wrong, either.

The most recent edition of The New Oxford American Dictionary added 2000 words to the English language, including “agritainment,” a noun that means “farm-based entertainment.”

Here in New Jersey, the term is closely related to “agrivation,” a feeling of exasperation that descends upon a single farm when thousands of city-dwellers cause traffic jams, create parking snafus, and empty an entire pumpkin patch so that the only form of entertainment left is a hayride to nowhere with two exhausted, disappointed children.

Thankfully we had a copy of Doreen Cronin and Betsy Lewin’s Click Clack Moo: Cows That Type in the car for the ride home. Now that’s the kind of funny farm we were looking for.

Hooray! More notes from the September NJ-SCBWI first page session!

Those familiar with peer critiques know the “sandwich” method: begin with what you liked, then move onto what needs work, and end by pointing out the manuscript’s merits. The editors followed this method well and offered compliments to soften the criticisms. Everyone must have left feeling good about an aspect of their writing. But we still have plenty to work on.

Some common suggestions:

- Rhyme carefully. Rhyme should have a consistent beat and meter. The editors easily picked out when a rhyme stretched to make it work. There was only one rhyming manuscript that worked. The other manuscripts felt limited by rhyme, and one in particular featured subject matter for an older audience, so the rhyme felt out of place. There’s a lot to live up to if you’re going to rhyme, so read many rhyming picture books to get a sense of how it all fits together. It’s not impossible, but great skill is required. They advised rewriting in prose and suggested using alliteration, which can be as fun as rhyming, without the restrictions. But use alliteration in moderation! (Umm, I didn’t mean to rhyme there…)

- Amp up the humor. The editors felt picture book laughs weren’t taken far enough. They wanted the stories to go from simply funny to outrageous. There’s always room for more humor. Make it crazier and more outlandish.

- Avoid common themes. Pets dying. New babies in the family. Monsters. Imaginary friends. First words. Retellings of The Three Little Pigs. These have all been done before, and done well. Stories on these subjects need to dig deep to find something new to say. Stand out, don’t blend in.

The editors also discussed avoiding clichés, clarifying the conflict on the first page, and cutting text to move action along faster. Out of 26 manuscripts, only two or three were considered strong contenders as written, and even so, they still required a little tweaking.

[An interesting tidbit for all you artists: if you’re an author/illustrator, consider yourself at an advantage. An editor is attracted to working with you since they skip the difficult step of matching your PB manuscript with an illustrator. Instead of communicating with two professionals to produce a book, the editor works directly with just one person—you.]

My friends and I thought that for the most part, both editors agreed on the manuscripts. However, one editor thought they didn’t agree very much at all!

But I think we can all agree that we need to work smarter. Some questions to think about as you work on your manuscript:

- Why should a publisher choose your story? What makes it unique and appealing, different from any other book in the marketplace?

- Why should a publisher spend tens of thousands of dollars, work several months (and in the case of PBs, years), and utilize the resources of a dozen or more staff members to produce your book?

- Is this truly the best story you can write? How can you make it even better?

Approximately 2.75 seconds after I tossed a rejection letter into an ever-growing “not right for our needs” pile, I opened this charming Mary Engelbreit card from a friend.

Approximately 2.75 seconds after I tossed a rejection letter into an ever-growing “not right for our needs” pile, I opened this charming Mary Engelbreit card from a friend.

Thank you, Marian.

Thank goodness the hand-written note has not become an extinct sentiment. Marian’s thoughtfulness erased my self-pity. One friend-fan who believes is all I need.

The day got even better when Val Webb emailed sketches of my new blog header. She’s incorporating the main character from one of my middle-grade novels-in-progress. I can’t wait to introduce you to her!

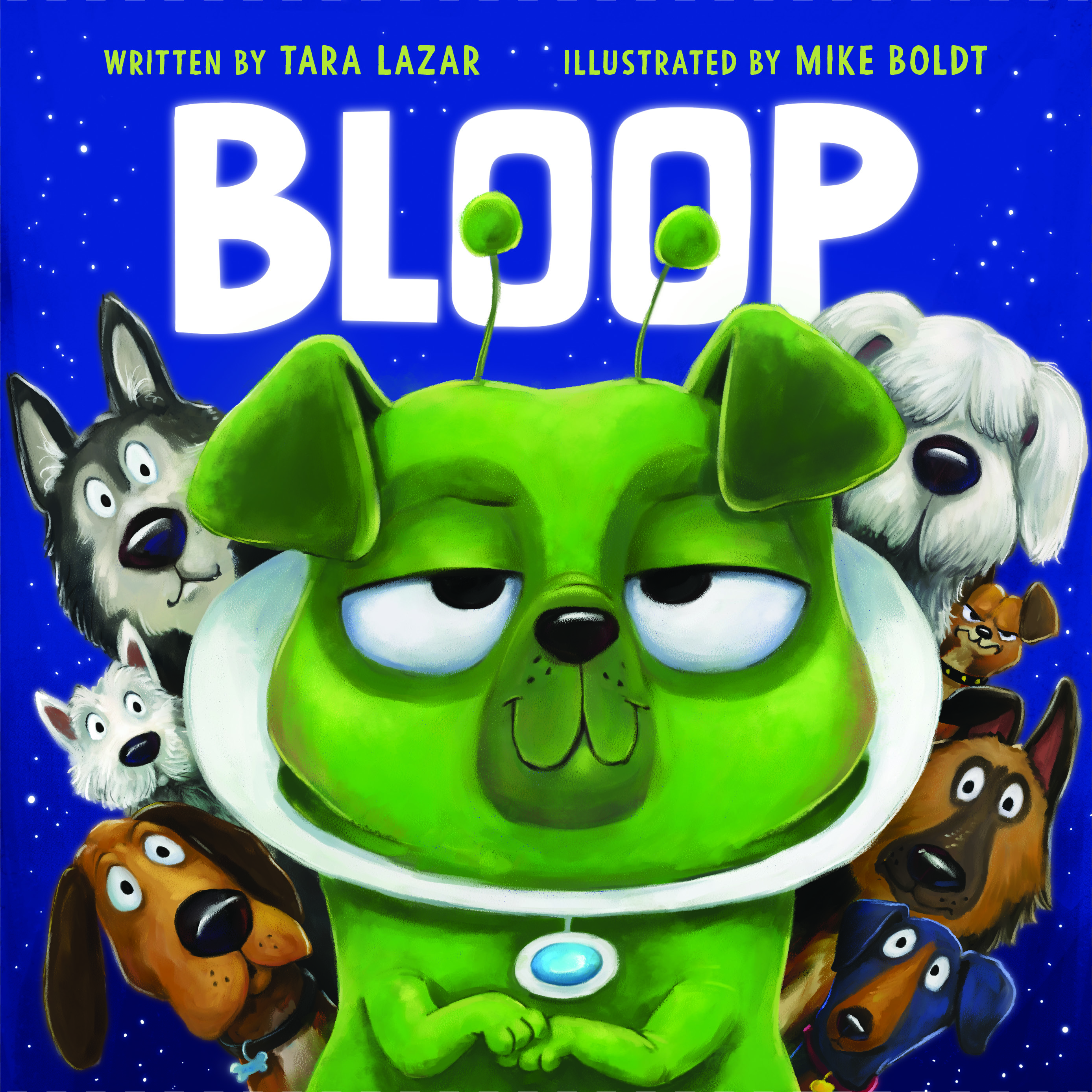

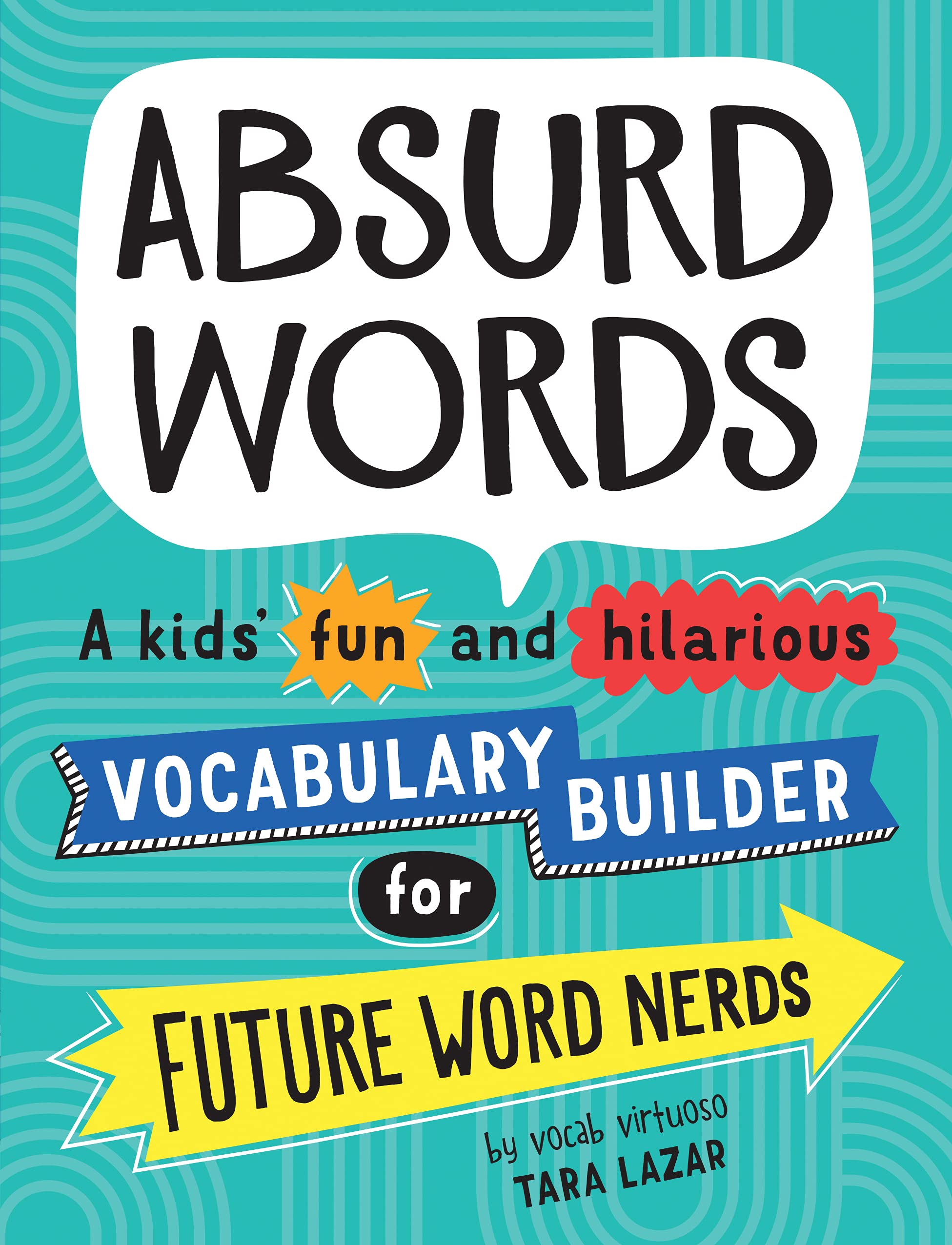

You’ve got less than fifteen seconds to grab a bookstore customer. That’s it. Your cover must lure them to the shelf. The title and design must call to them. Fail this instant judgment test and lose a sale. Yep, they really do judge a book by its cover.

So do kids. My Kindergartener cannot read, but she knows what books she wants. Last week she came home with a list of book fair titles she had selected on her own, solely by the covers. I decided to research the books before deciding whether to buy.

Without exception, every book cover featured a pony or a dog. Yes, she loves both animals. But the one book that she begged for the most? My Chincoteague Pony by Susan Jeffers.

How could a horse-crazed little girl resist? A black-and-white filly seems to be smiling as waves splash around her. The two-toned pink background and glitter on both the letters and the water seal the deal.

How could a horse-crazed little girl resist? A black-and-white filly seems to be smiling as waves splash around her. The two-toned pink background and glitter on both the letters and the water seal the deal.

The story inside proves to be just as charming as the cover. Julie works hard on the family farm all year, earning money to buy her own pony at the annual Chincoteague auctions. The cover exudes a certain promise to the reader, and it delivers.

In contrast, another horse-themed picture book attracted my attention, but my daughter passed it by. The brown, muted tones of Twenty Heartbeats by Dennis Haseley reflects this story’s more mature vibe.

A wealthy man commissions a master artist to paint a portrait of his favorite horse. Years pass without word from the artist and the man grows angry. Yet the artist does not deliver until he feels the painting is the best he can produce. The book’s message is one of hard work, patience and perseverance, but the lesson needed to be explained to my child whereas she immediately grasped Julie’s work ethic in My Chincoteague Pony.

A wealthy man commissions a master artist to paint a portrait of his favorite horse. Years pass without word from the artist and the man grows angry. Yet the artist does not deliver until he feels the painting is the best he can produce. The book’s message is one of hard work, patience and perseverance, but the lesson needed to be explained to my child whereas she immediately grasped Julie’s work ethic in My Chincoteague Pony.

There could be several reasons for this, none having to do with the cover. For instance, the main character in Jeffers’ tale is a young girl from present time, easily relatable. The main characters in Twenty Heartbeats are adult men from ancient China.

In the end, I purchased both books, although I admit, Twenty Heartbeats was more for me than it was for her.

I wonder if publishers design some book covers to appeal more to the adult-gatekeepers than to the direct audience. This would make sense if a book contains mature themes and universal lessons that parents wish to teach their children.

There are some book covers that both my daughter and I agree upon. Here are just a few that we would like to read together. (Please note that Savvy is a middle-grade novel. But what a gorgeous, eye-catching cover.)