You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Writing for Children’ category.

This is the first in a series of posts on the 2008 Rutgers University Council on Children’s Literature One-on-One Mentoring Conference. (Because I have 20 pages of notes to share!)

Phew! What a whirlwind day! I mingled with editors, mixed with agents, and milled about with other aspiring authors at the RUCCL mentoring conference. My head is spinning with suggestions. So where to start? Well, I’ll begin at the end, with keynote speaker K.L. Going. The author of Fat Kid Rules the World and The Liberation of Gabriel King wrapped up the event with an inspiring speech about “writing across the lines.”

Agent Linda Pratt introduces K.L. Going

K.L. began by telling us what we already know: as writers, we have many, many rules to follow. Manuscript length. Formatting. Submission guidelines. Avoid passive voice. Don’t write didactic tales.

“But writers are creative souls,” she said. “It’s hard for us to color within the lines.”

She stopped her speech and asked everyone to stand up. And then she told us to shake off those rules! So I grabbed my friend Jill by the shoulders and shimmied her around. She returned the favor. Wubba wubba wubba! Boy, that felt good!

“Despite what anyone else says,” she said, “there are times you must step across those lines.” She relayed her early writing experience, sitting on the floor of her sparse employee housing at Mohonk Mountain House, typing away on her laptop. It was the happiest time in her life because she wrote without rules. She didn’t care if anyone read her work, she simply wrote because that’s what brought her the most joy. She wasn’t thinking about marketability, high-concept hooks, or the current list of best-sellers. However, it was also the least productive time in her life since she wasn’t writing with that intention to sell.

So how can writers be both happy and productive? You need to choose which lines you’re willing to cross while staying inside others. With Fat Kid Rules the World, she wanted to create a character that wasn’t familiar. Troy is dirty, smelly and raw. And to some, offensive. That was a line she was willing to cross, potentially alienating some readers. But, she still wanted Troy to be lovable by the end of the book. She could not compromise on that essential rule of writing: creating likeable characters.

“You need to write what you want regardless of whether you think anyone else ‘gets it’,” she said. “But writing what you desire is always a risk.” With Fat Kid, she didn’t necessarily cater to the reader. There’s a hunk of bleeding leg and splattering of fat when Troy envisions the results of his own suicide, and some people may put the book down at that point. (In fact, her book was banned in some areas.) But others will stick with it and read on. If the reader’s journey isn’t easy, maybe it will be more redemptive and satisfying by the end.

“You need to write what you want regardless of whether you think anyone else ‘gets it’,” she said. “But writing what you desire is always a risk.” With Fat Kid, she didn’t necessarily cater to the reader. There’s a hunk of bleeding leg and splattering of fat when Troy envisions the results of his own suicide, and some people may put the book down at that point. (In fact, her book was banned in some areas.) But others will stick with it and read on. If the reader’s journey isn’t easy, maybe it will be more redemptive and satisfying by the end.

She cautioned us further: you need to balance your risks. Troy may be unusual, but his emotional struggles are immediately known in the first chapter. Readers may not relate to his appearance, but they can relate to the critical inner voice we’ve all had whispering in our ears at some time in our lives.

K.L. told us it’s important to know the rules. Because you can only make educated decisions about your manuscript when you have knowledge of the industry. “But don’t forget that creativity has its own demands. Don’t be afraid to try something different. Step boldly across the lines!”

So, where are the lines for you?

Last week Nathan Bransford asked blog readers to tell him about the worst piece of writing advice they ever received. I didn’t participate because I couldn’t think of anything. Sure, there was the critique partner who rewrote my manuscript in her own style. Yeah, I’ve been told a story was ready for submission only to realize, months later, that it needed more work. And a writing professor once banned the entire class from killing off characters. He didn’t want us to come to a rough patch in our story and take the easy way out. I didn’t agree with the rule, but it was understandable.

I don’t consider any of that bad advice. Poor judgment, maybe, but not faulty guidance (especially since I didn’t follow it).

The best advice is not really advice at all, but when a publishing professional relates his or her own experience to an aspiring author. Advice is subjective; it’s based upon personal circumstances. If you don’t know the story behind the advice, then it’s impossible to gauge whether or not that advice will work for you.

So don’t give advice. Tell others what you’ve learned and how you’ve learned it. Share your experience.

The children’s writing world is filled with many generous professionals who volunteer their time to assist those of us starting out. Never before have I met such a kind and welcoming group of people. I have to say that no one has given me a bad piece of advice yet. And hopefully I won’t steer you wrong, either.

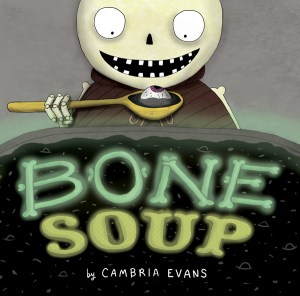

Succulent eyeballs float among tender bat wings, seasoning Cambria Evans’ Bone Soup with gross Halloween humor no five year-old can resist.

Succulent eyeballs float among tender bat wings, seasoning Cambria Evans’ Bone Soup with gross Halloween humor no five year-old can resist.

The main character Finnigin has a reputation for being a greedy eater. So when the witch finds out he’s coming to town, she warns her beastly neighbors. Everyone stashes their groceries away, hiding toenail clippings, frogs legs, and other ghoulish gourmet ingredients. No one offers him a bite to eat, not even a nibble of wormy cheese.

So the hungry, resourceful Finnigin boils a cauldron in town square. Into the bubbling pot he drops one dry bone, claiming it will create a magical delicacy. Of course, the curious creatures can’t help but add to the brew, and soon everyone is feasting on slimy gruel thickened with dried mouse droppings. Yum!

Evans’ pen-and-watercolor illustrations strike just the right balance between spooky and funny. The mummy wears a pretty pink bow and the werewolf looks more like a harmless hedgehog. The green and brown color palate makes every page feel like it’s glowing in the dark, adding to the fun Halloween spirit.

Stone Soup has been retold many times, but never with so much disgusting deliciousness.

History Lessons

Juliet Dupree snuck into Mr. Forman’s classroom before the morning bell and wrote Mr. Snoreman on the blackboard. When Tristan sat next to her, she’d nudge his arm, nod toward the front of the room, and take credit.

Everyone knew that Mr. Forman’s monotone lectures came straight from the textbook, word for dreary word. He cradled the teacher’s guide with his left arm while he pointed to the ceiling with his right, appearing only slightly more animated than the Statue of Liberty.

The huddled masses of 1st period American History yearned to be free of boredom, so Tristan organized daily pranks. Yesterday the entire class dropped their textbooks on the floor at precisely 8:10am…and received empty detention threats at 8:11am.

When Juliet reached for her book, she had noticed it was published the year she was born. That was odd; she was pretty certain that something historically meaningful had happened in the past 13 years. After all, Tristan had kissed her. That might not make it into the next edition of An American Account Volume II, but it would launch an unpredictable new chapter in her own history, threatening full-out war as soon as Tristan’s girlfriend found out.

This flash fiction piece is in response to the Imagine Monday writing prompt posted last Friday. Join us every week for a new writing exercise.

When I came up with this week’s prompt, I immediately drifted back to my 9th grade American History class. The tale above isn’t far from what occurred in the classroom. My friend arranged pranks on a near-daily basis. One day a classmate discovered that he owned the same digital Casio watch as our teacher, so he set the alarm to go off in class. Our teacher fumbled at his wrist, wondering why he couldn’t get the beeping to stop. Such adolescent nonsense has a way of escalating into legend, and in the hyperbole of memory, I recall this little trick baffling our teacher for months.

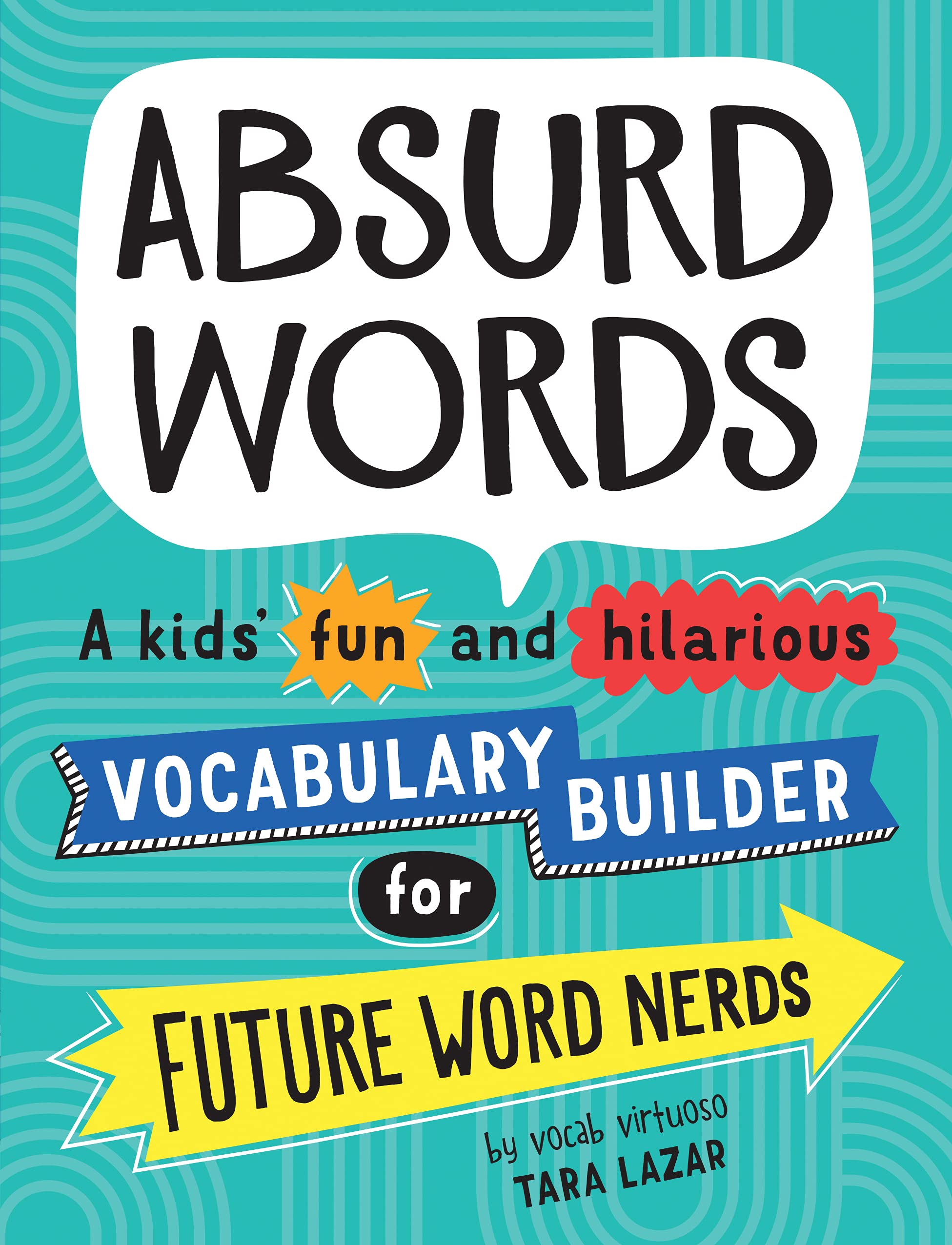

The most recent edition of The New Oxford American Dictionary added 2000 words to the English language, including “agritainment,” a noun that means “farm-based entertainment.”

Here in New Jersey, the term is closely related to “agrivation,” a feeling of exasperation that descends upon a single farm when thousands of city-dwellers cause traffic jams, create parking snafus, and empty an entire pumpkin patch so that the only form of entertainment left is a hayride to nowhere with two exhausted, disappointed children.

Thankfully we had a copy of Doreen Cronin and Betsy Lewin’s Click Clack Moo: Cows That Type in the car for the ride home. Now that’s the kind of funny farm we were looking for.

Hooray! More notes from the September NJ-SCBWI first page session!

Those familiar with peer critiques know the “sandwich” method: begin with what you liked, then move onto what needs work, and end by pointing out the manuscript’s merits. The editors followed this method well and offered compliments to soften the criticisms. Everyone must have left feeling good about an aspect of their writing. But we still have plenty to work on.

Some common suggestions:

- Rhyme carefully. Rhyme should have a consistent beat and meter. The editors easily picked out when a rhyme stretched to make it work. There was only one rhyming manuscript that worked. The other manuscripts felt limited by rhyme, and one in particular featured subject matter for an older audience, so the rhyme felt out of place. There’s a lot to live up to if you’re going to rhyme, so read many rhyming picture books to get a sense of how it all fits together. It’s not impossible, but great skill is required. They advised rewriting in prose and suggested using alliteration, which can be as fun as rhyming, without the restrictions. But use alliteration in moderation! (Umm, I didn’t mean to rhyme there…)

- Amp up the humor. The editors felt picture book laughs weren’t taken far enough. They wanted the stories to go from simply funny to outrageous. There’s always room for more humor. Make it crazier and more outlandish.

- Avoid common themes. Pets dying. New babies in the family. Monsters. Imaginary friends. First words. Retellings of The Three Little Pigs. These have all been done before, and done well. Stories on these subjects need to dig deep to find something new to say. Stand out, don’t blend in.

The editors also discussed avoiding clichés, clarifying the conflict on the first page, and cutting text to move action along faster. Out of 26 manuscripts, only two or three were considered strong contenders as written, and even so, they still required a little tweaking.

[An interesting tidbit for all you artists: if you’re an author/illustrator, consider yourself at an advantage. An editor is attracted to working with you since they skip the difficult step of matching your PB manuscript with an illustrator. Instead of communicating with two professionals to produce a book, the editor works directly with just one person—you.]

My friends and I thought that for the most part, both editors agreed on the manuscripts. However, one editor thought they didn’t agree very much at all!

But I think we can all agree that we need to work smarter. Some questions to think about as you work on your manuscript:

- Why should a publisher choose your story? What makes it unique and appealing, different from any other book in the marketplace?

- Why should a publisher spend tens of thousands of dollars, work several months (and in the case of PBs, years), and utilize the resources of a dozen or more staff members to produce your book?

- Is this truly the best story you can write? How can you make it even better?

Approximately 2.75 seconds after I tossed a rejection letter into an ever-growing “not right for our needs” pile, I opened this charming Mary Engelbreit card from a friend.

Approximately 2.75 seconds after I tossed a rejection letter into an ever-growing “not right for our needs” pile, I opened this charming Mary Engelbreit card from a friend.

Thank you, Marian.

Thank goodness the hand-written note has not become an extinct sentiment. Marian’s thoughtfulness erased my self-pity. One friend-fan who believes is all I need.

The day got even better when Val Webb emailed sketches of my new blog header. She’s incorporating the main character from one of my middle-grade novels-in-progress. I can’t wait to introduce you to her!

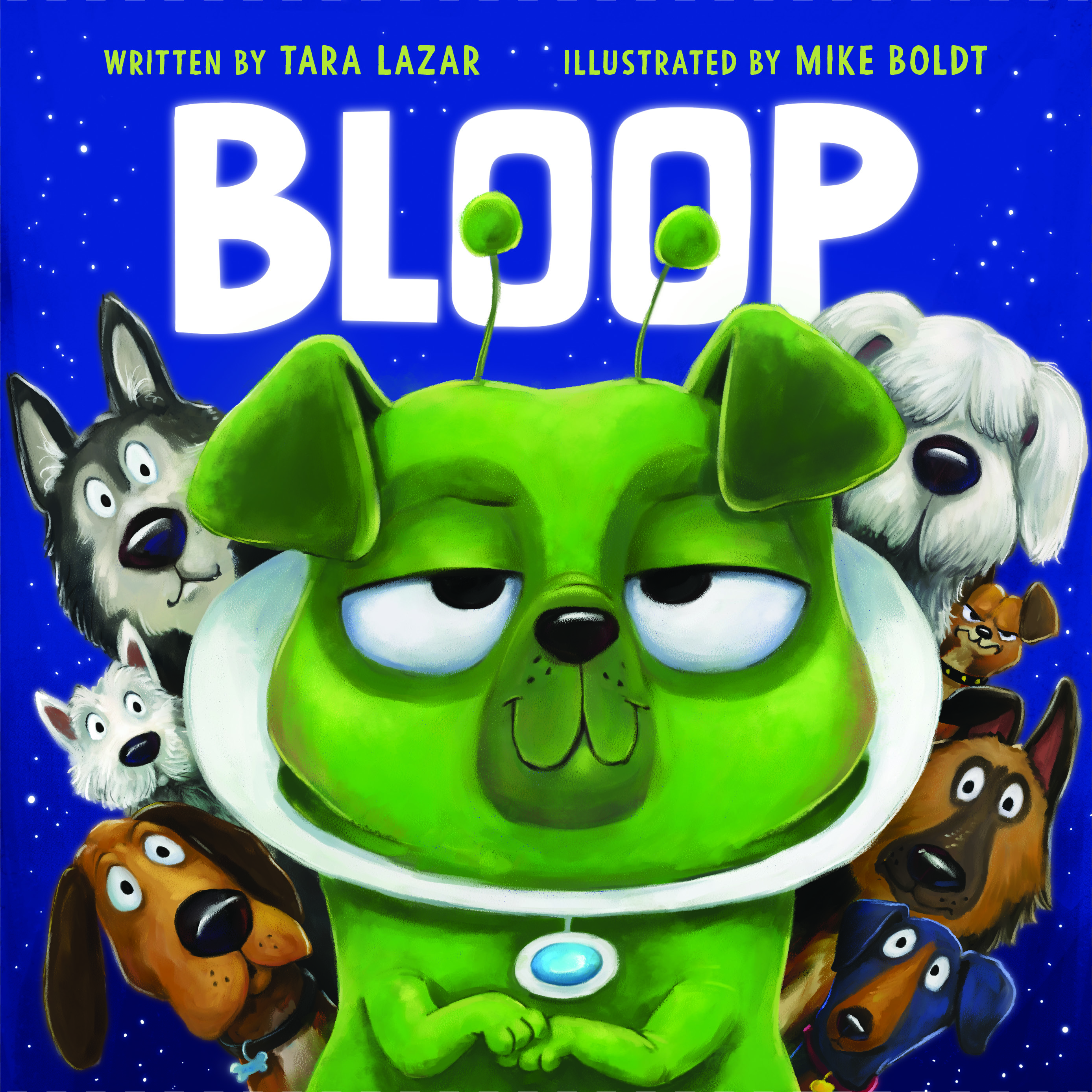

You’ve got less than fifteen seconds to grab a bookstore customer. That’s it. Your cover must lure them to the shelf. The title and design must call to them. Fail this instant judgment test and lose a sale. Yep, they really do judge a book by its cover.

So do kids. My Kindergartener cannot read, but she knows what books she wants. Last week she came home with a list of book fair titles she had selected on her own, solely by the covers. I decided to research the books before deciding whether to buy.

Without exception, every book cover featured a pony or a dog. Yes, she loves both animals. But the one book that she begged for the most? My Chincoteague Pony by Susan Jeffers.

How could a horse-crazed little girl resist? A black-and-white filly seems to be smiling as waves splash around her. The two-toned pink background and glitter on both the letters and the water seal the deal.

How could a horse-crazed little girl resist? A black-and-white filly seems to be smiling as waves splash around her. The two-toned pink background and glitter on both the letters and the water seal the deal.

The story inside proves to be just as charming as the cover. Julie works hard on the family farm all year, earning money to buy her own pony at the annual Chincoteague auctions. The cover exudes a certain promise to the reader, and it delivers.

In contrast, another horse-themed picture book attracted my attention, but my daughter passed it by. The brown, muted tones of Twenty Heartbeats by Dennis Haseley reflects this story’s more mature vibe.

A wealthy man commissions a master artist to paint a portrait of his favorite horse. Years pass without word from the artist and the man grows angry. Yet the artist does not deliver until he feels the painting is the best he can produce. The book’s message is one of hard work, patience and perseverance, but the lesson needed to be explained to my child whereas she immediately grasped Julie’s work ethic in My Chincoteague Pony.

A wealthy man commissions a master artist to paint a portrait of his favorite horse. Years pass without word from the artist and the man grows angry. Yet the artist does not deliver until he feels the painting is the best he can produce. The book’s message is one of hard work, patience and perseverance, but the lesson needed to be explained to my child whereas she immediately grasped Julie’s work ethic in My Chincoteague Pony.

There could be several reasons for this, none having to do with the cover. For instance, the main character in Jeffers’ tale is a young girl from present time, easily relatable. The main characters in Twenty Heartbeats are adult men from ancient China.

In the end, I purchased both books, although I admit, Twenty Heartbeats was more for me than it was for her.

I wonder if publishers design some book covers to appeal more to the adult-gatekeepers than to the direct audience. This would make sense if a book contains mature themes and universal lessons that parents wish to teach their children.

There are some book covers that both my daughter and I agree upon. Here are just a few that we would like to read together. (Please note that Savvy is a middle-grade novel. But what a gorgeous, eye-catching cover.)