You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘Linda Ravin Lodding’ tag.

by Linda Ravin Lodding

Some days, the world feels like it’s shouting in ALL CAPS.

You open the news and there it is again: another story that makes your shoulders creep toward your ears like they’re trying to become earrings. Another big, complicated grown-up problem. Another reason to refresh your coffee.

And if you write for children, there’s an extra layer—because while adults read the news, kids absorb it.

- Through snippets of conversation.

- Through the temperature of a room.

- Through the way we say, “It’s fine,” while our eyebrows disagree.

Children don’t need us to hand them the whole scary world, fully assembled, with all the sharp corners sticking out.

But they do deserve stories that help them name what they sense—stories that don’t slam the door on hard topics, but crack a window open just enough to let in air.

And maybe… a little laughter.

Because picture books—small as they are—are mighty.

- They are portable courage.

- They are a hand to hold.

- They are a way of saying: Yes, the world can be a lot. But you are not alone inside it.

Over the years, I’ve found myself drawn to stories that matter—stories that let children practice compassion, curiosity, and courage.

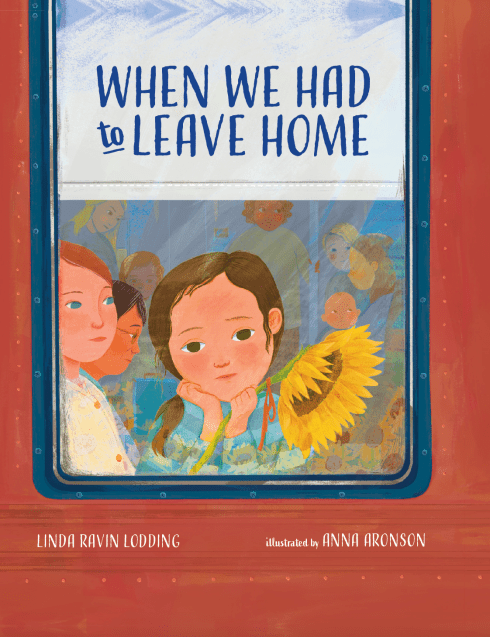

Stories like WHEN WE HAD TO LEAVE HOME, about the refugee experience of leaving a place you love and trying to carry “home” inside you when everything has changed.

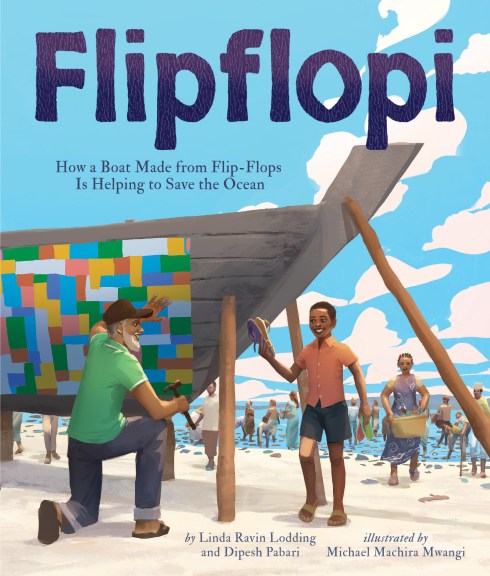

Or FLIPFLOPI: How a Boat Made from Plastic Is Helping to Save the World’s Oceans, which takes a huge issue (plastic waste, the ocean, the future!) and turns it into something tangible: a real-life boat made from flip-flops, a problem turned into possibility.

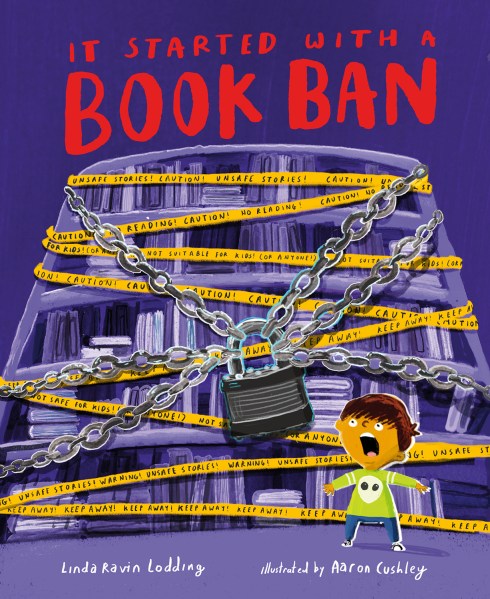

And now, with my upcoming picture book IT STARTED WITH A BOOK BAN (Albert Whitman, April 9, 2026), I’m stepping into another headline-sized topic—book banning—through a very kid-sized door.

So how do you take something huge…and make it holdable?

When I look back over my shoulder, I realize I return to the same technique again and again when I’m trying to transform a headline into a hopeful story idea. This is my headline-to-heart structure:

Step 1: The World Problem (a.k.a. the grown-up thundercloud)

Start with the big issue—the “headline.” Not the whole tangled mess of it. Just the core.

- Books are being challenged.

- Families have to move.

- The ocean is filling with plastic.

- A new kid arrives and no one knows what to do with different.

At this stage, it’s too big. Too abstract. Too… adults yelling on the internet.

So we shrink it.

Step 2: The Kid Goal (a.k.a. one small mission with a big heartbeat)

Now translate the world problem into one child’s clear mission.

- Not a message. Not a lesson.

- A mission.

- Because stories don’t begin with themes.

- They begin with a character who wants something.

And for picture books, I love giving kids one simple action word:

save / find / fix / keep / share

In IT STARTED WITH A BOOK BAN, the world problem might be “banned books,” but the story lives at kid-level: a child trying to protect stories the way kids protect treasures. The tone I aimed for wasn’t “lecture in disguise.” It was humor and absurdity as the flashlight—the kind that makes a difficult topic feel safe enough to explore.

- Because kids understand unfair.

- They understand someone took my thing

- They understand why does that grown-up get to decide?

And they also understand the delightfully ridiculous “logic” of bans that spiral until the town is banning the color green, birdsong, and even the satisfying pop of bubble wrap.

In WHEN WE HAD TO LEAVE HOME, the headline is displacement—but the kid-goal becomes intimate and specific: hold on to one familiar thing… a sunflower. That’s how kids survive big change: one small anchor at a time.

And in FLIPFLOPI, the world problem is enormous (the ocean!), but the kid mission is wonderfully concrete: make something new from what was thrown away. It’s a story of action, ingenuity, and that thrilling moment when kids realize:

Wait… we can DO something?

(And the joy here is that it’s based on the real-life Flipflopi Project in Lamu, Kenya. In virtual school visits, children from around the world get to “visit” the boatyard and watch flip-flops transform into a boat—trash into treasure, problem into possibility.)

- When you give a child character a clear mission, the story shifts from doom to motion.

- And motion is hope.

Step 3: The Warm Twist Ending (a.k.a. hope with muddy shoes)

Finally, look for an ending that offers a warm turn—one that feels earned.

- Not a tidy bow.

- A real shift.

Maybe the twist is:

- Community (someone joins in)

- Laughter (a misunderstanding turns sweet)

- Imagination (the kid re-frames the problem)

- A small win (that matters because it’s theirs)

The child doesn’t fix the whole world.

But the child proves something essential:

I am not powerless inside it.

And that—quietly—is what we’re doing as children’s writers. We’re offering young readers practice in empathy. In courage. In the ability to look at a complicated world and still say:

- I can be kind.

- I can be curious.

- I can do something small.

And that small thing counts.

Try It Today: Your StorySpark

Pick a headline theme:

- books

- moving

- ocean plastic

- new kid

Give your character ONE mission:

- save

- find

- fix

- share

Add one emotional obstacle (the real engine of story!):

- fear

- embarrassment

- jealousy

- loneliness

- the desperate wish to be “normal”

Because the best picture books aren’t actually about the issue.

They’re about the heart inside the issue.

Linda Ravin Lodding is  an award-winning children’s author who believes picture books can be a warm hug, a bright flashlight, and a good giggle—especially when the world feels a little too loud. She’s has eleven published picture books, including The Busy Life of Ernestine Buckmeister, A Gift for Mama, Painting Pepette, and Babies Are Not Bears. Originally from New York and now based in Stockholm, Sweden, Linda is also a writing coach who has helped over 100 picture book writers find their storytelling voice, and she founded the Stockholm Children’s Writers and Illustrators Network (a Facebook community open to all!). By day, she serves as Head of Communications at Global Child Forum, championing children’s rights worldwide. Her newest picture book, IT STARTED WITH A BOOK BAN (Albert Whitman & Co.), releases April 9, 2026. Follow her on Instagram @lindaravinlodding_author.

an award-winning children’s author who believes picture books can be a warm hug, a bright flashlight, and a good giggle—especially when the world feels a little too loud. She’s has eleven published picture books, including The Busy Life of Ernestine Buckmeister, A Gift for Mama, Painting Pepette, and Babies Are Not Bears. Originally from New York and now based in Stockholm, Sweden, Linda is also a writing coach who has helped over 100 picture book writers find their storytelling voice, and she founded the Stockholm Children’s Writers and Illustrators Network (a Facebook community open to all!). By day, she serves as Head of Communications at Global Child Forum, championing children’s rights worldwide. Her newest picture book, IT STARTED WITH A BOOK BAN (Albert Whitman & Co.), releases April 9, 2026. Follow her on Instagram @lindaravinlodding_author.

Here’s the problem with doing a PiBoIdMo blog post at the end of the month:

I was going to write about setting. But Tammi did that.

I was going to doodle. But Debbie already did that.

I was going to send you an Inspiration Fairy. But Courtney already sent you one.

I thought about chicken nuggets. But so did Sudipta.

So, what’s left?

Endings! Big, bold, surprising, clever, tender, awww-inspiring endings!

As we ease into the final stretch of PiBoIdMo, like you, I have a list of ideas. Some I’ve even started writing. But none of them have endings. (Yet.)

Many of us experience the first flush of excitement when a new idea tickles us until we have to put words down on paper. We have an idea! A character! A setting! Maybe we even have conflict! But, if you’re like me, you hope that by the time you hit the 700 word mark the ending will just write itself. But here’s the problem with endings that just write themselves. They’re usually flat.

And no wonder. A great ending is as difficult to write as an opening sentence. And as important.

Here’s what’s on an ending’s “to do list”:

- An ending has to resolve the story problem in a satisfying way (no plot points still hanging);

- It has to have the main character solving the conflict by the last page;

- It should either be predictable enough to emotionally resonate with the reader or unpredictable enough to delight;

- If it’s a humorous picture book it needs to deliver the final punch line;

- And, like a fine wine (or peanut butter fluffernutter sandwich), it needs to linger on your reader’s palette long after the meal in consumed.

So let’s think of how we can use page 32 to offer the perfect ending to your story.

Here are some possibilities:

Surprise Ending

Think beyond the obvious ending and offer the reader a surprise – the opposite of what’s expected. It should still be logical, but it doesn’t have to be inevitable. Emma Dodd does that in “What Pet to Get” as does Cynthia Rylant in “The Old Woman Who Named Things.” Both offer surprise endings but do so in very different ways.

Circular Ending

In my picture book OSKAR’S PERFECT PRESENT (2013), Oskar starts his journey looking for the perfect present for his mother. On the first page, he finds it—a perfect rose! But as Oskar makes subsequent trades along his journey home, he is left without a present. On the last page, however, he is reunited with the same rose he traded away at the start of his journey. Circular endings—or those that somehow mirror the opening—are among my favorite endings since they offer closure in an often clever way.

Fulfillment

Sometimes a last page is simply the climax of the story, the fulfillment of the character’s desire. In “When Marion Sang”, Pam Munoz Ryan’s book about opera singer Marion Andresen, Marion is denied to sing on many American stages because she was African American. The last page of the story reads, “. . .and Marian sang.” In my picture book THE BUSY LIFE OF ERNESTINE BUCKMEISTER, Ernestine is the queen of over-scheduled set, and she just wants to play. In the end, she does just that and the final words, “And sometimes she just played,” underscore that Ernestine is fulfilled.

Wordless

And ending can be wordless, relying on a single-spread illustration to close the story. While the ending is wordless, it still needs to be “written” within the visual. This type of ending can be used effectively in both quiet books and humorous books. In a quiet book, the ending visual might be a sunset, an embrace, a child sleeping. In a funny book the last illustration can hint at a visual joke or twist. In my picture book HOLD THAT THOUGHT, MILTON (2012) the final joke is embedded within the illustration which hints that just when the reader thought all was back to normal…it isn’t.

I love working on my endings. It never ceases to amaze me how changing the ending can change the entire feel of the previous pages.

You know when you go to a movie and it finishes? If it’s been a good movie, you want to stay seated in the darkened theater suspended in the magic of the story. You want to draw out the experience just a little longer. A picture book ending should do the same thing for the reader. It should offer the reader that all-important pause (for reflection, a hug, or a giggle) before they close the book.

What kind of endings do you like? What fits best with your story? What kind of ending gives your story a unique slant? Try out alternative endings and see how the mood, the rhythm, the idea of the book changes. And revise until you find your happily ever after…

Linda has spent the past 15 years living in Stockholm, Vienna and now The Netherlands. She lives in a one-windmill town with her husband and 13 year-old daughter and helped to establish the country’s first SCBWI chapter. Her picture book, The Busy Life of Ernestine Buckmeister (illustrated by Suzanne Beaky, Flashlight Press), debuted in October and was noted in the ABC Best Books Catalog 2011. Her next two picture books—Hold That Thought, Milton! (illustrated by Ross Collins) and Oskar’s Perfect Present (illustrated by Alison Jay) will be coming out in 2012 and 2013. And when she’s not working on her beginnings, middles and endings, she’s a public information consultant with the United Nations. Visit Linda at: www.lindalodding.com.

Linda has spent the past 15 years living in Stockholm, Vienna and now The Netherlands. She lives in a one-windmill town with her husband and 13 year-old daughter and helped to establish the country’s first SCBWI chapter. Her picture book, The Busy Life of Ernestine Buckmeister (illustrated by Suzanne Beaky, Flashlight Press), debuted in October and was noted in the ABC Best Books Catalog 2011. Her next two picture books—Hold That Thought, Milton! (illustrated by Ross Collins) and Oskar’s Perfect Present (illustrated by Alison Jay) will be coming out in 2012 and 2013. And when she’s not working on her beginnings, middles and endings, she’s a public information consultant with the United Nations. Visit Linda at: www.lindalodding.com.

by

by