You are currently browsing Tara Lazar’s articles.

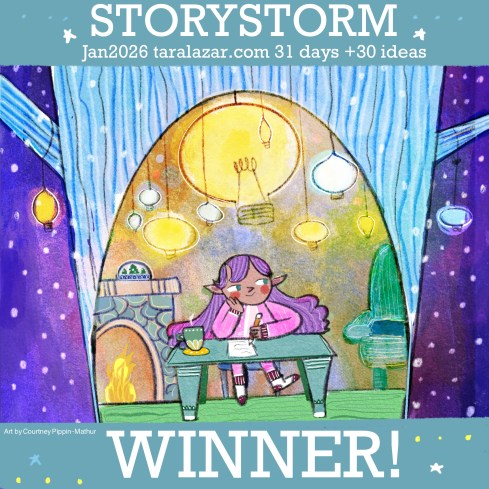

If you’ve been participating in Storystorm all month, you’ve been gathering a flurry of ideas!

Luckily you don’t need a blizzard of ideas to “win” the Storystorm challenge. You just need 30 of them!

When you have 30 ideas, you can qualify to win one of the AMAZING Storystorm Grand Prizes—feedback on your best 5 picture book ideas from a kidlit agent! (List to be announced.)

SWEET!

In order to qualify for a Grand Prize, your name must be on the registration post AND the pledge below.

If you have 30 ideas, put your right hand on a picture book and repeat after me:

I do solemnly swear that I have faithfully executed

the Storystorm 30-ideas-in-January challenge,

and will, to the best of my ability,

parlay my ideas into picture book manuscripts.

Now I’m not saying all 30 ideas have to be good. Some may just be titles, some may be character quirks. Some may be problems and some may create problems when you sit down to write. Some may be high-concept and some barely a concept. But…they’re yours, all yours!

You have until February 7th at 11:59:59PM EST to sign the pledge by leaving a comment on this post.

PLEASE COMMENT ONLY ONCE.

The name you left on the registration post and the name you leave on this winner’s pledge SHOULD MATCH. However, when you comment, WordPress also logs other info that allows me to recognize you, so don’t worry if they’re not exact.

Again, please COMMENT ONLY ONCE. If you make a mistake, contact me instead of leaving a second comment.

Also, please know that sometimes WP puts your comment into a queue that I must moderate and approve, so it may take 24 hours (or more) for your comment to actually appear.

Remember, this is an honor system pledge. You don’t have to send in your ideas to prove you’ve got 30 of them. If you say so, I’ll believe you! Honestly, it’s that simple. (Wouldn’t it be nice if real life were that straightforward.)

Before you sign, you can also pick up your Winner’s Badge by illustrator Courtney Pippin-Mathur!

(Right click to download, then upload it anywhere!)

There are winner’s mugs at Zazzle.com/store/storystorm. All proceeds go to Boyds Mills (formerly The Highlights Foundation). If there’s other SWAG you want, I can add it to the shop…just ask!

Now…are you ready to sign?

Then GO FOR IT! Let’s see your name below!

And, CONGRATULATIONS!

That’s right, it’s the last day of Storystorm! Bonus day to get to 30 ideas!

Tomorrow I’ll post the Storystorm Pledge where you can confirm you have at least 30 bright and beautiful new story ideas. Just comment on tomorrow’s thread and say “YES!”

Remember, don’t send your ideas to me. Don’t post them online. This is all on the honor system. If you say you have 30 ideas, I’ll believe you!

Here are some useful posts from previous Storystorms to guide you to the finish line!

Oh yeah, they’re all by Tammi Sauer, who was the first author to ever say “YES!” when I asked her to guest blog. Thanks, Tammi!

by Nikki Grimes

Where did you get the idea for your story? That’s probably the most commonly posed question asked of authors. The truth is, no two answers are the same, at least not for me.

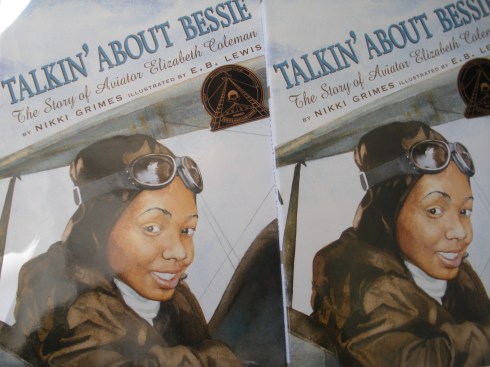

Some ideas are seeded by research. Years ago, an editor asked if I would consider writing a picture book about a little known Black historical figure. I didn’t have any in mind, so I took a stroll through my encyclopedia to see if there was any subject who interested me. That’s where I initially encountered Bessie Coleman, the first Black woman pilot. Delving into her story led to my picture book biography, TALKIN’ ABOUT BESSIE, illustrated by E.B. Lewis.

My research about Bessie revealed that her father was Native American, of the Choctaw Nation. That research note inspired my forthcoming picture book, STRONGER THAN, a story about a Black Choctaw character named Dante. The book is written in collaboration with Choctaw author Stacy Wells and illustrated by E.B. Lewis. (The background of this collaborative work is a story in and of itself, but that’s for another day.)

There are countless untold stories of remarkable men, women, and children available for the telling, if we look for them. Bonus? These stories come with built-in characters, plot lines, and time frames—perfect building blocks for solid storytelling. There are also seeds for stories found in history (CHASING FREEDOM, my picture book about Harriet Tubman and Susan B. Anthony, for example), science and nature (Joyce Sidmon and Jeannine Atkins often draw from these), and more.

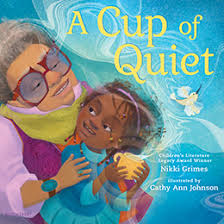

Before you go digging into history, biography, or science though, remember that there are stories parading through your own mind, clamoring for attention, if you’ll only listen. My latest picture book, A CUP OF QUIET, was one of those.

I love the quality of quiet found in nature. I must have thought and spoken those very words a thousand times, over the years, without every stopping to notice the story possibilities nestled inside of them. But then, a couple of years ago, I finally did. On that day, I started digging, and that meant asking questions.

I love the quality of quiet found in nature. I must have thought and spoken those very words a thousand times, over the years, without every stopping to notice the story possibilities nestled inside of them. But then, a couple of years ago, I finally did. On that day, I started digging, and that meant asking questions.

What was it about the quality of that quiet that I loved? What sounds created it? In what kind of spaces did I notice those sounds? How did that kind of quiet make me feel? Each question led to a myriad of answers, and I jotted them all down. Those answers led me to the doorstep of inspiration: Why not write a story about a child discovering the quality of quiet found in nature? Once I had that nugget, I was off and running.

The inspiration of A CUP OF QUIET had been patiently waiting inside my mind—and outside in my garden—all along. How many ideas are roaming around in your mind, waiting for your attention? What are some of the things you think, or say, all the time? When you think about it, chances are you’ll discover more than a few. Pick one and hone in on it. Ask some questions. Do some digging in the garden of your mind, and find the rose patiently waiting for you!

—from A CUP OF QUIET

New York Times bestselling author Nikki Grimes has received the CSK Virginia Hamilton Lifetime Achievement Award, the ALAN Award for adolescent literature, the Children’s Literature Legacy Medal, the NCTE Award for Excellence in Poetry for Children, and the Coretta Scott King Award for Bronx Masquerade. Other titles include Printz Honor and Sibert Honor winner Ordinary Hazards, ALA Notable Legacy:Women Poets of the Harlem Renaissance and picture books Southwest Sunrise, Kirkus Best Book Bedtime for Sweet Creatures, Kamala Harris: Rooted in Justice, Lullaby for the King, A Walk in the Woods, and A Cup of Quiet. Ms. Grimes lives in Corona, California. You can follow her on Instagram @poetrynikki and Bluesky @poetnikki.

New York Times bestselling author Nikki Grimes has received the CSK Virginia Hamilton Lifetime Achievement Award, the ALAN Award for adolescent literature, the Children’s Literature Legacy Medal, the NCTE Award for Excellence in Poetry for Children, and the Coretta Scott King Award for Bronx Masquerade. Other titles include Printz Honor and Sibert Honor winner Ordinary Hazards, ALA Notable Legacy:Women Poets of the Harlem Renaissance and picture books Southwest Sunrise, Kirkus Best Book Bedtime for Sweet Creatures, Kamala Harris: Rooted in Justice, Lullaby for the King, A Walk in the Woods, and A Cup of Quiet. Ms. Grimes lives in Corona, California. You can follow her on Instagram @poetrynikki and Bluesky @poetnikki.

by Johanna Peyton

In my family, I’ve been dubbed the Director of Champagne because I love finding big and small moments to celebrate.

When my son with a speech-delay said his name for the first time, we made a special trip for ice cream cones. When my daughter completed her dyslexia reading intervention, we surprised her with confetti cannons and sparklers. When it’s been a long week but it’s only Tuesday, we blast music and have a dance party. And if it’s your birthday, you better believe there are celebration candles in whatever you’re eating for breakfast, lunch, dinner, and dessert!

Celebrations make life more fun, but they also encourage gratitude, spark appreciation of others, and recognize growth. But maybe most importantly, they give us all a chance to slow down and take notice of the moment.

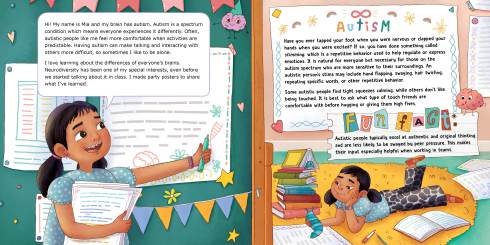

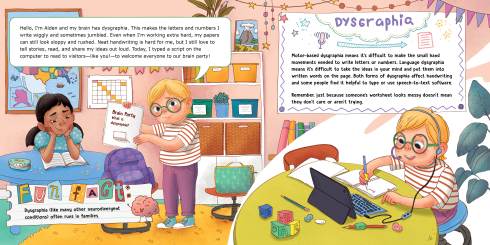

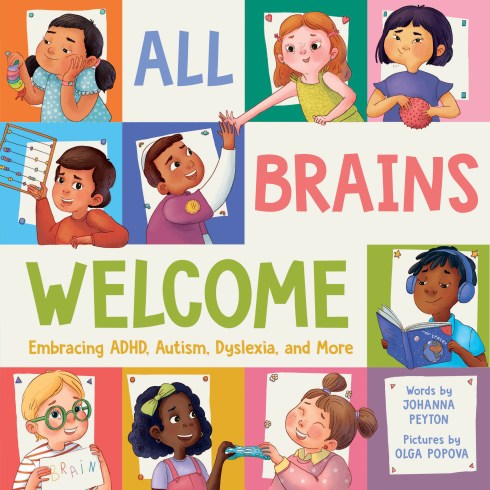

It will probably come as no surprise that my debut nonfiction picture book is about a celebration. ALL BRAINS WELCOME: Embracing ADHD, Autism, Dyslexia, and More is a celebratory look at neurodivergence through a classroom brain party. It is illustrated by Olga Popova and comes out in October with Sourcebooks eXplore. You can help me start the celebration now by preordering a copy wherever books are sold!

The spark for this book came from my own family’s brain parties. This was our way of celebrating our children’s brains as they each received different neurodivergent diagnoses. For us, this looked like going out to my kids’ favorite restaurants, ordering dessert first, and telling the servers we were celebrating our brains! We got some funny looks, but it gave us a dedicated time and space to talk about feelings and next steps, all while surrounding our kids in positivity and support.

Taking inspiration from my family’s celebrations, in ALL BRAINS WELCOME we meet a class full of children who show readers how their brains work in different ways: creative and colorful, careful and focused, or fast and full of ideas. Together, they’re throwing a class brain party and celebrating what makes each of them unique. It’s joyful, informative, and with a clear message that no matter what kind of brain you have, there is a place for you at this party, because the world needs every kind of thinker.

I’m excited to be able to share an early glimpse of a few of the internal spreads, which are so new they are still in process!

What about you? What things do you or your kids celebrate? Or what unique celebrations did your family have growing up? I encourage you to think outside of holiday festivities to celebrations that have become family lore. The odder, the better.

Maybe it’s growth milestones, like giving away a pacifier to the paci-fairy? Or when a child is finally able to land a full cartwheel or flip? (Actually, this just reminded me of the water watch-party my older daughter hosted with neighbors to show off the younger two kids mastering their swim team flip turns. Ridiculous–and so fun! Hmmm… maybe there is a story there?)

- Or a celebration of imagination, like finding a fairy house or a witch’s lair?

- Or maybe it’s celebrating a failure because that means you or a child tried and grew?

- Or maybe it’s something you wish was celebrated but was overlooked? How did that make you feel?

Now, how could you expand that celebratory moment to make sure it appeals to children of today?

Although not technically a brainstorming exercise, I would be a lousy Director of Champagne if I didn’t encourage everyone to celebrate a writing win today…

You have made it all the way to DAY 29 of this challenge–Congratulations!! You now have 29 sparkly new story ideas!

Cue cheers and confetti! Yay you!

Johanna Peyton is a proudly neurodivergent author who writes with playfulness and poignancy. She holds a BBA in Marketing and Entrepreneurial Management and an MPH in Health Promotion and Behavioral Science. When she isn’t writing, Johanna works as a literacy and dyslexia advocate with local nonprofits. She lives in Austin, TX, with her husband, their three kids, and their dog, cat, horse, and bees! To learn more about Johanna and her work, visit JohannaPeyton.com or connect with her on Instagram @JohannaPeytonAuthor or Bluesky @johannapeyton.bsky.social.

Johanna Peyton is a proudly neurodivergent author who writes with playfulness and poignancy. She holds a BBA in Marketing and Entrepreneurial Management and an MPH in Health Promotion and Behavioral Science. When she isn’t writing, Johanna works as a literacy and dyslexia advocate with local nonprofits. She lives in Austin, TX, with her husband, their three kids, and their dog, cat, horse, and bees! To learn more about Johanna and her work, visit JohannaPeyton.com or connect with her on Instagram @JohannaPeytonAuthor or Bluesky @johannapeyton.bsky.social.

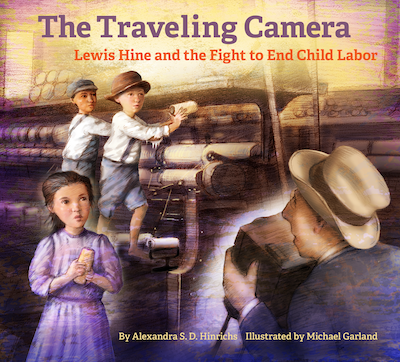

by Alexandra Hinrichs

I let the weeds grow in my yard. Dandelions, hawkweed, wood violets, white clover, red clover, sow thistle, blue sowthistle, ground elder. At first this began because my spouse and I couldn’t be bothered—or afford—to maintain a lawn. Then we noticed how much the honeybees loved the weeds. Over time, we planted more flowers, many native to Maine, and, along with our three kids, delighted in watching butterflies and hummingbirds arrive. And then, around our 16th wedding anniversary, we adopted a tortoise. It turns out her favorite foods are weeds like dandelions, clover, and thistle. With the occasional bonus treat of calendula, hibiscus, and other delectable blooms.

So why am I talking about weeds with a foot of snow on the ground outside of my window? Well, I let the weeds grow in my mind, too. A higgledy-piggledy clutter of ideas, often unidentifiable when they first poke their green heads up from the earth of my brain. I have learned to let them be, at least for a time, observe how they grow. Will they send shoots off sideways and spread? Will they strive upward and point their hopes sunward, sometimes growing as tall as me? Will petals unfurl? Will they hold the big surprise of the tiniest, palest, sweetest imaginable berry? I watch. I wait. I see what else they nourish. Because like the weeds in my yard, some of those wilds in my brain attract company. Characters who crawl or creep, flutter or fly, skip or saunter over. And suddenly there’s a story.

Years ago, when it still was a big combination of smooshed-together-coupled letters, Storystorm helped me cultivate a practice of watching the weeds. Of paying attention and jotting down brief thoughts in the form of a list that lives in my ever so drab Notes app. I always tell kids during author visits that I wish I were one of those cool authors who has a notebook I whip out of a pocket as needed, but I’d lose a notebook in a heartbeat. My phone works for me, and doing what works, what feels easy, has made all the difference in the world. Now it takes me a long while to scroll to the bottom of that list of ideas, which is organized simply by year. There are hundreds. It’s the nature journaling of my mind.

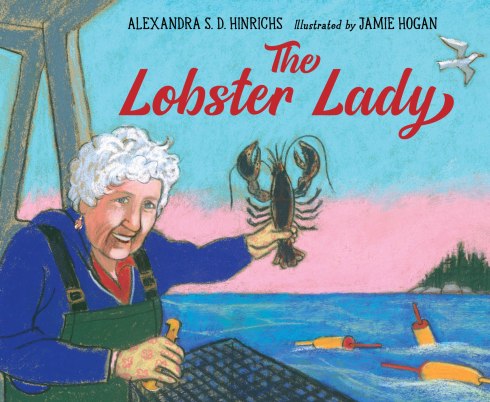

But not all ideas grow equally. Some grow and bloom quickly, demanding my attention. THE LOBSTER LADY, illustrated by Jamie Hogan, was like that. I had the idea on July 17, 2021, met Virginia Oliver (who passed away at 105 years of age last week) the next day, sent the manuscript to my agent within a week.

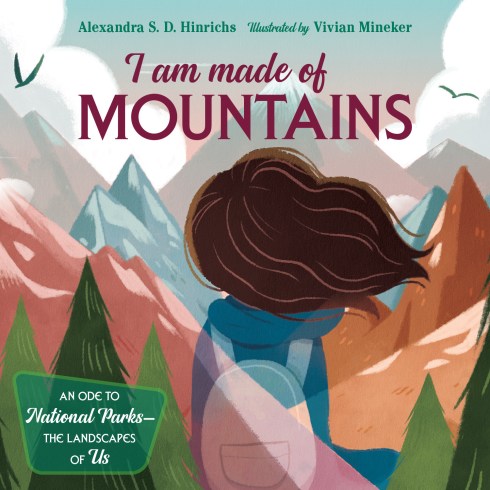

Some ideas have a strong start but need a little extra care. I AM MADE OF MOUNTAINS, illustrated by Vivian Mineker was like that. While it always had the rhyming voice celebrating a multiplicity of people, landscapes, and emotions, its structure and even bringing in National Parks came later.

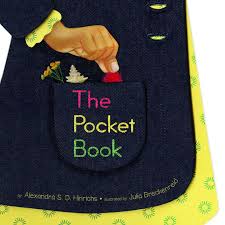

Some ideas are seeds planted that I forget about until a year or multiple years have passed. THE POCKET BOOK, illustrated by Julia Breckenreid, was one such seed. I wrote a few words down about the idea in 2018: “pocketful of love—remnants of the day’s love full moments.” It stayed planted, fertile, sending out shoots for another three years. Then I finally wrote the story in 2021 to get a monthly draft done for the 12×12 Challenge, and it grew with gusto.

The seed for THE TRAVELING CAMERA was planted when I learned about Lewis Hine’s photographs of child labor in graduate school in 2010. Those powerful images stayed with me, nudged me.

My next book, THE SEARCH FOR A UNICORN, which will come out in 2028, emerged quickly but was another idea that needed tending to fully bloom. I started writing it the same day I had the idea in 2019, finished a draft in 2020, and it took another two years before a key part of the story clicked into place for me and helped me sell the manuscript thanks to research. Yup, research for a unicorn story! But actually, that research sort of bumped into me accidentally. I hadn’t set out to find it, but happened upon it and explored the questions it caused me to ask, explored the possibility that maybe, maybe, it could nourish my draft. My precious weed.

So yes, let the weeds grow. It may look messy and unkempt in the landscapes of our brains, but wow, the robust stories that emerge! The unexpected colors and blooms and sure, occasional thorns! And hey, while you’re at it, pay attention to those weeds at your feet, too. You never know where you might find the seed of an idea.

Alexandra Hinrichs is the Children’s Book Editor at Islandport Press, where she acquires board books through young adult fiction and nonfiction. She is also the author of THE LOBSTER LADY, I AM MADE OF MOUNTAINS, THE POCKET BOOK, THE TRAVELING CAMERA, and more. Her books have won awards including Maine’s Lupine Award and Wisconsin’s Outstanding Achievement Award. They’ve been featured on ABC News, CBS News, and The Washington Post. Alex began her career as a historical researcher at American Girl and then worked as a librarian for over a decade. She lives in Maine with her husband, three wild sons, two lazy cats, and one curious tortoise. Visit her website at AlexandraHinrichs.com. You can follow her on Instagram @puddlereader and BlueSky @puddlereader.

Alexandra Hinrichs is the Children’s Book Editor at Islandport Press, where she acquires board books through young adult fiction and nonfiction. She is also the author of THE LOBSTER LADY, I AM MADE OF MOUNTAINS, THE POCKET BOOK, THE TRAVELING CAMERA, and more. Her books have won awards including Maine’s Lupine Award and Wisconsin’s Outstanding Achievement Award. They’ve been featured on ABC News, CBS News, and The Washington Post. Alex began her career as a historical researcher at American Girl and then worked as a librarian for over a decade. She lives in Maine with her husband, three wild sons, two lazy cats, and one curious tortoise. Visit her website at AlexandraHinrichs.com. You can follow her on Instagram @puddlereader and BlueSky @puddlereader.

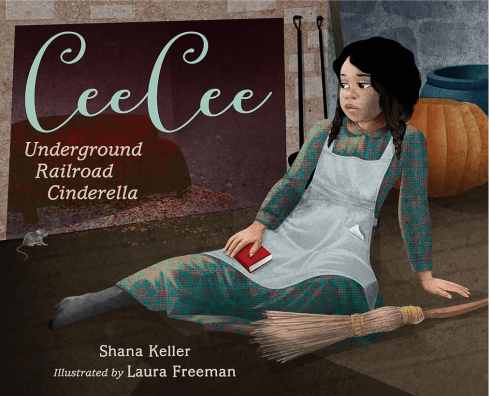

by Shana Keller

Not all ideas arrive fully formed. Sometimes inspiration strikes like lightning—sudden, intense, and impossible to ignore. Other times it comes quietly, like a feeling that lingers long after the moment has passed.

CEECEE, UNDERGROUND RAILROAD CINDERELLA was one of those quieter ideas.

After rearranging my bookshelves for the millionth time (it’s an obsessive hobby), I fixated on an old Disney copy of Cinderella. I kept the book on my desk for a while, knowing I wanted to write a Cinderella story that featured someone who looked like me. And how could I honor the story I loved, while making it my own?

The Disney version had left a strong imprint on me as a child, and I couldn’t quite imagine what a new angle would even be.

A few months later, I scrolled across Vashti Harrison’s gorgeous illustration of a young Black girl in what looked, to me, like a Cinderella dress. Yes! I thought, feeling closer to the idea. The image stayed with me, but the story still eluded me. Yet the need to write it—whatever it was—wouldn’t go away. Frustrated, I put it on the back burner. Again.

Then, several months later, I read a story that changed everything.

It was an imagined conversation between Harriet Tubman and Susan B. Anthony. In it, Harriet described rescuing a young girl from a life of bondage. Suddenly, all the pieces clicked.

That’s the thing about ideas: they don’t always arrive with a clear purpose. Sometimes they come to you as questions you don’t yet know how to answer.

The Cinderella story I thought I knew wasn’t about waiting for rescue at all. It was about the courage to escape. It was about a girl who refused to accept a life that was forced on her. It was about self-determination, resilience, and the fierce truth that you can rescue yourself—if you’re willing to step into the unknown.

That’s how my retelling was born: a Cinderella who was enslaved, who didn’t wait for a prince, and who didn’t need anyone to grant her freedom. She didn’t need a glass slipper to prove her worth. She only needed a plan, a fierce heart, and the belief that she could become her own hero.

If there’s one thing I’ve learned from this journey, it’s this: when something catches your eye—when an image or a line or a character’s face sticks with you—don’t dismiss it just because you don’t know what it means yet. And don’t force it into a story before it’s ready. Hold onto it. Keep it close. Let it sit in the back of your mind.

Because ideas have their own timing.

Some will arrive like lightning, demanding immediate attention. Others will whisper, then wait patiently for you to be ready. The quiet ones often take longer—but they tend to stay. And when the pieces finally fall into place, you’ll realize the story was inside you all along.

Shana Keller grew up a middle child in Middle America wondering exactly how clouds stayed in the air. She’s traveled all over the country and some parts of Europe with her family, and moved too many times to count. She is the author of multiple picture books including the Irma Black Honor, BREAD FOR WORDS, A Frederick Douglass Story and TICKTOCK BANNEKER’S CLOCK, rated a Best STEM book by the Children’s Book Council. You can visit her at ShanaKeller.com and on Instagram @shanakellerwrites.

Shana Keller grew up a middle child in Middle America wondering exactly how clouds stayed in the air. She’s traveled all over the country and some parts of Europe with her family, and moved too many times to count. She is the author of multiple picture books including the Irma Black Honor, BREAD FOR WORDS, A Frederick Douglass Story and TICKTOCK BANNEKER’S CLOCK, rated a Best STEM book by the Children’s Book Council. You can visit her at ShanaKeller.com and on Instagram @shanakellerwrites.

Don’t worry kids, there’s no remote learning today! It’s a true snow day to play.

Go to Snowdays.me and create a snowflake!

When posting your flurry flake, write “Storystorm” in the “What’s Your Message?” box. Then everyone can do a search to find and view the Storystorm snowflakes!

As you can see, I’ve been doing this for many years!

In the meantime…

…remember the feeling of anticipation, waiting for the phone to ring at 5:30AM on a winter morning? And when it did, you knew you could turn off your alarm and dive deeper into the blankets. School is closed! Sledding, snowmen and hot cocoa await!

Can you recapture that combination of euphoria and freedom in a story?

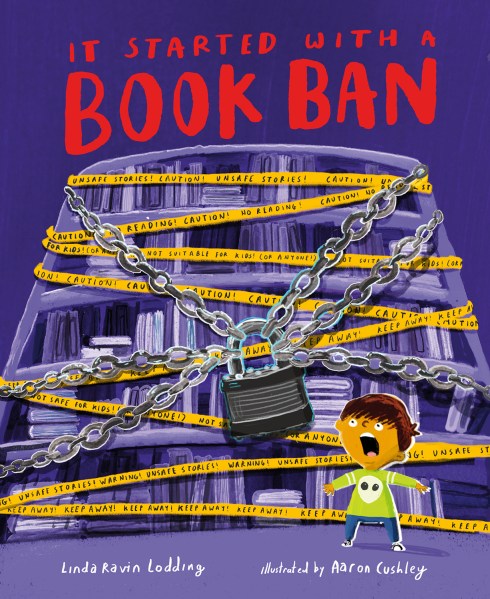

by Linda Ravin Lodding

Some days, the world feels like it’s shouting in ALL CAPS.

You open the news and there it is again: another story that makes your shoulders creep toward your ears like they’re trying to become earrings. Another big, complicated grown-up problem. Another reason to refresh your coffee.

And if you write for children, there’s an extra layer—because while adults read the news, kids absorb it.

- Through snippets of conversation.

- Through the temperature of a room.

- Through the way we say, “It’s fine,” while our eyebrows disagree.

Children don’t need us to hand them the whole scary world, fully assembled, with all the sharp corners sticking out.

But they do deserve stories that help them name what they sense—stories that don’t slam the door on hard topics, but crack a window open just enough to let in air.

And maybe… a little laughter.

Because picture books—small as they are—are mighty.

- They are portable courage.

- They are a hand to hold.

- They are a way of saying: Yes, the world can be a lot. But you are not alone inside it.

Over the years, I’ve found myself drawn to stories that matter—stories that let children practice compassion, curiosity, and courage.

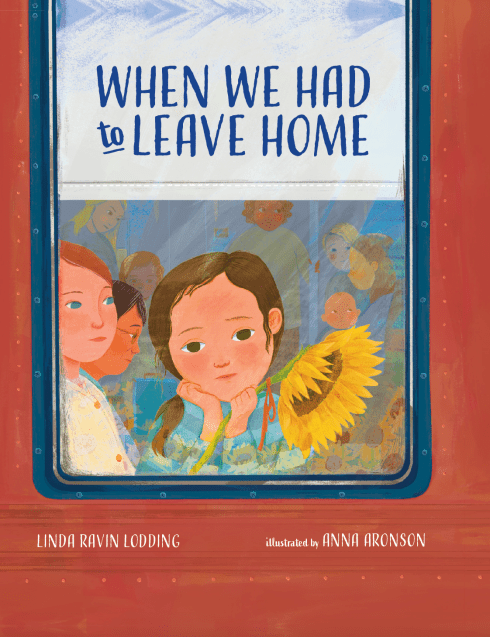

Stories like WHEN WE HAD TO LEAVE HOME, about the refugee experience of leaving a place you love and trying to carry “home” inside you when everything has changed.

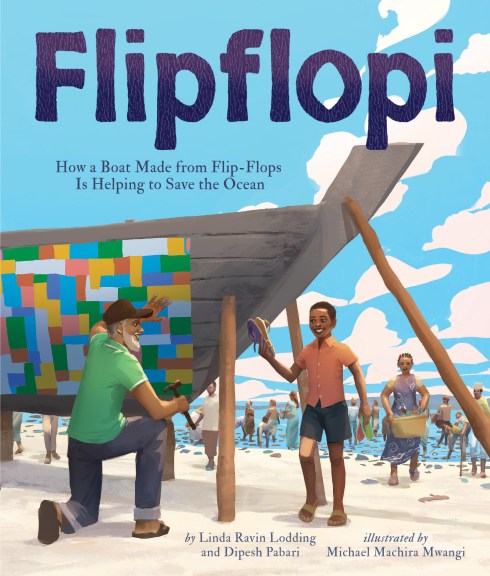

Or FLIPFLOPI: How a Boat Made from Plastic Is Helping to Save the World’s Oceans, which takes a huge issue (plastic waste, the ocean, the future!) and turns it into something tangible: a real-life boat made from flip-flops, a problem turned into possibility.

And now, with my upcoming picture book IT STARTED WITH A BOOK BAN (Albert Whitman, April 9, 2026), I’m stepping into another headline-sized topic—book banning—through a very kid-sized door.

So how do you take something huge…and make it holdable?

When I look back over my shoulder, I realize I return to the same technique again and again when I’m trying to transform a headline into a hopeful story idea. This is my headline-to-heart structure:

Step 1: The World Problem (a.k.a. the grown-up thundercloud)

Start with the big issue—the “headline.” Not the whole tangled mess of it. Just the core.

- Books are being challenged.

- Families have to move.

- The ocean is filling with plastic.

- A new kid arrives and no one knows what to do with different.

At this stage, it’s too big. Too abstract. Too… adults yelling on the internet.

So we shrink it.

Step 2: The Kid Goal (a.k.a. one small mission with a big heartbeat)

Now translate the world problem into one child’s clear mission.

- Not a message. Not a lesson.

- A mission.

- Because stories don’t begin with themes.

- They begin with a character who wants something.

And for picture books, I love giving kids one simple action word:

save / find / fix / keep / share

In IT STARTED WITH A BOOK BAN, the world problem might be “banned books,” but the story lives at kid-level: a child trying to protect stories the way kids protect treasures. The tone I aimed for wasn’t “lecture in disguise.” It was humor and absurdity as the flashlight—the kind that makes a difficult topic feel safe enough to explore.

- Because kids understand unfair.

- They understand someone took my thing

- They understand why does that grown-up get to decide?

And they also understand the delightfully ridiculous “logic” of bans that spiral until the town is banning the color green, birdsong, and even the satisfying pop of bubble wrap.

In WHEN WE HAD TO LEAVE HOME, the headline is displacement—but the kid-goal becomes intimate and specific: hold on to one familiar thing… a sunflower. That’s how kids survive big change: one small anchor at a time.

And in FLIPFLOPI, the world problem is enormous (the ocean!), but the kid mission is wonderfully concrete: make something new from what was thrown away. It’s a story of action, ingenuity, and that thrilling moment when kids realize:

Wait… we can DO something?

(And the joy here is that it’s based on the real-life Flipflopi Project in Lamu, Kenya. In virtual school visits, children from around the world get to “visit” the boatyard and watch flip-flops transform into a boat—trash into treasure, problem into possibility.)

- When you give a child character a clear mission, the story shifts from doom to motion.

- And motion is hope.

Step 3: The Warm Twist Ending (a.k.a. hope with muddy shoes)

Finally, look for an ending that offers a warm turn—one that feels earned.

- Not a tidy bow.

- A real shift.

Maybe the twist is:

- Community (someone joins in)

- Laughter (a misunderstanding turns sweet)

- Imagination (the kid re-frames the problem)

- A small win (that matters because it’s theirs)

The child doesn’t fix the whole world.

But the child proves something essential:

I am not powerless inside it.

And that—quietly—is what we’re doing as children’s writers. We’re offering young readers practice in empathy. In courage. In the ability to look at a complicated world and still say:

- I can be kind.

- I can be curious.

- I can do something small.

And that small thing counts.

Try It Today: Your StorySpark

Pick a headline theme:

- books

- moving

- ocean plastic

- new kid

Give your character ONE mission:

- save

- find

- fix

- share

Add one emotional obstacle (the real engine of story!):

- fear

- embarrassment

- jealousy

- loneliness

- the desperate wish to be “normal”

Because the best picture books aren’t actually about the issue.

They’re about the heart inside the issue.

Linda Ravin Lodding is  an award-winning children’s author who believes picture books can be a warm hug, a bright flashlight, and a good giggle—especially when the world feels a little too loud. She’s has eleven published picture books, including The Busy Life of Ernestine Buckmeister, A Gift for Mama, Painting Pepette, and Babies Are Not Bears. Originally from New York and now based in Stockholm, Sweden, Linda is also a writing coach who has helped over 100 picture book writers find their storytelling voice, and she founded the Stockholm Children’s Writers and Illustrators Network (a Facebook community open to all!). By day, she serves as Head of Communications at Global Child Forum, championing children’s rights worldwide. Her newest picture book, IT STARTED WITH A BOOK BAN (Albert Whitman & Co.), releases April 9, 2026. Follow her on Instagram @lindaravinlodding_author.

an award-winning children’s author who believes picture books can be a warm hug, a bright flashlight, and a good giggle—especially when the world feels a little too loud. She’s has eleven published picture books, including The Busy Life of Ernestine Buckmeister, A Gift for Mama, Painting Pepette, and Babies Are Not Bears. Originally from New York and now based in Stockholm, Sweden, Linda is also a writing coach who has helped over 100 picture book writers find their storytelling voice, and she founded the Stockholm Children’s Writers and Illustrators Network (a Facebook community open to all!). By day, she serves as Head of Communications at Global Child Forum, championing children’s rights worldwide. Her newest picture book, IT STARTED WITH A BOOK BAN (Albert Whitman & Co.), releases April 9, 2026. Follow her on Instagram @lindaravinlodding_author.

by Kaz Windness

If you’re like me you have LOTS of book ideas. Too many at times. My ideas almost always start with a doodle in my sketchbook. But how do I decide which ideas are worth writing stories for? Which characters have the best chance of becoming a published book?

That’s where “high concept” comes in. I define high concept as “a striking and easily communicable idea.”

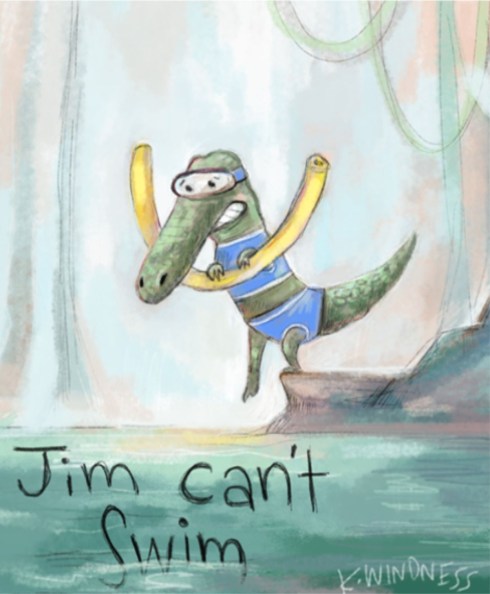

What if a child is afraid of the water? That could be a good story, but it’s expected. It doesn’t hook you in the way a crocodile who’s afraid of the water might.

This is the doodle that later became “Swim, Jim!” I got the idea from a news article about a real crocodile using a pool noodle to cross a canal in Florida.

Being a neurodivergent child in a classroom has become a more commonplace story, but what if that experience is explained by a bat in a classroom for mice? That was how “Bitsy Bat, School Star” began.

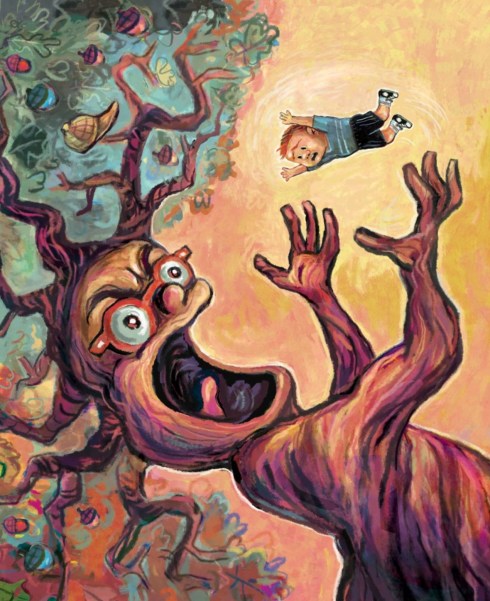

Dealing with bullies? Expected. Turning into a tree monster and eating your bully? That’s the hook in “Ollie, the Acorn, and the Mighty Idea,” written by Andrew Hacket, illustrated by me.

An easy way to come up with a “high concept” idea is to mash two popular or funny topics together in an unexpected way. I got series deals for both of these mashups:

- Cat + Spy = TUX GUY, CAT SPY

- Chickens + Time Travel = TIME TRAVELING CHICKENS: BAWK TO THE FUTURE

This hook hunt is easily turned into a writing game. Let’s play!

First, write down ten characters. Then, write down ten professions. There will be crossover, but the idea is to get some ideas flowing.

Here’s what I came up with:

Characters

- A Smelly Sock

- A Sentient Rutabaga

- Lost Stick of ChapStick

- An Extremely Small Alien

- A Gigantic Cat

- A Cowboy

- A Sleepy Jack-O-Lantern

- A Lost Aardvark

- A Barnyard Peacock

Professions

- Professional Wrestler

- A Garbage Truck Driver

- Super Hero

- Dog-Catcher

- A Farmer

- Milkman

- Weightlifter

- Astronaut

- Underpants Connoisseur

- Chef

Now, mash some of these together. Some examples:

- A ChapStick Wrestler: Battling a big pair of chapped lips maybe?

- A Cowboy Astronaut: Wrangling the stars atop a space ship named Horse?

- A Gigantic Cat Milkman: What happens when they drink the world out of milk?

Next, pick a mashup that’s piquing your curiosity and identify the problem. What will the character lose if they don’t solve their problem? A character without a problem or a desire isn’t very fun to read.

Example based on Cowboy Astronaut:

Why would a cowboy astronaut need to wrangle the stars? Have the stars lost their [milky] way?

Here’s a premise (logline) formula I use to figure out what the story and stakes might be:

Formula:

In a (SETTING)

a (PROTAGONIST)

has a (PROBLEM)

(caused by an ANTAGONIST)

and (faces CONFLICT)

as they try to (achieve a GOAL).

In deep space (SETTING), a cowboy astronaut (PROTAGONIST) must return a posse of stars (PROBLEM) scattered by a space storm (ANTAGONIST) back to their constellations so he can find his home planet before supper (GOAL).

This is obviously not the best story idea ever, but if you do enough of these, you’ll eventually hit gold.

What did you come up with? Happy writing!

Kaz Windness is the award-winning, genre-crossing illustrator and author of funny and heart-warming books for young readers. Proudly neurodivergent (ASD/ADHD), Kaz specializes in character-driven books celebrating inclusivity, grit, and kindness. Her many books include the Geisel Honor recipient, “Worm and Caterpillar are Friends,” the Dolly Parton Imagination Library selection, “When You Love a Book,” and the acclaimed autism acceptance Bitsy Bat series. Kaz taught illustration at the Rocky Mountain College of Art + Design for 12+ years and is the founder of The Cuddlefish Academy, where she inspires students to tell stories with pictures. Kaz lives in Colorado with her English-teacher husband, two teenage children, and a bunny-obsessed Boston Terrier named Remy. Kaz loves making deep-dish pizza from scratch and sketching animals at the zoo.

Kaz Windness is the award-winning, genre-crossing illustrator and author of funny and heart-warming books for young readers. Proudly neurodivergent (ASD/ADHD), Kaz specializes in character-driven books celebrating inclusivity, grit, and kindness. Her many books include the Geisel Honor recipient, “Worm and Caterpillar are Friends,” the Dolly Parton Imagination Library selection, “When You Love a Book,” and the acclaimed autism acceptance Bitsy Bat series. Kaz taught illustration at the Rocky Mountain College of Art + Design for 12+ years and is the founder of The Cuddlefish Academy, where she inspires students to tell stories with pictures. Kaz lives in Colorado with her English-teacher husband, two teenage children, and a bunny-obsessed Boston Terrier named Remy. Kaz loves making deep-dish pizza from scratch and sketching animals at the zoo.

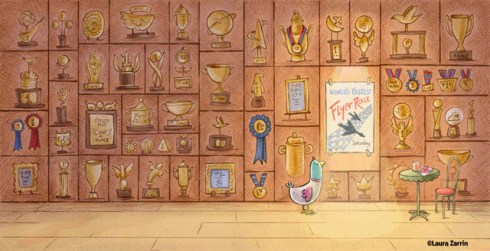

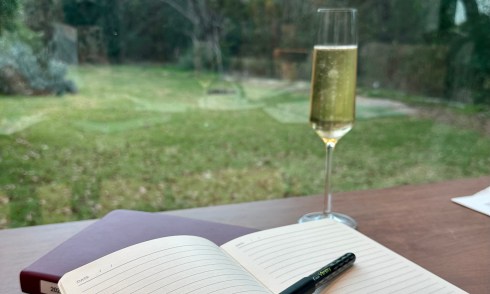

by Laura Zarrin

I’ve been an artist all of my life, but even though I liked writing, I never considered myself an author. That changed thanks to Storystorm, but making time to write without distractions has been a huge problem for me.

I have all kinds of tricks to keep my butt in the chair while illustrating. I binge TV shows or listen to audio books while I draw and paint. It’s the perfect job! I can’t listen to music, because I start choreographing dances in my head (former dancer here). I have had some luck listening to Bridgerton music. Writing requires silence. I dread the silence and find myself avoiding writing. Whole days go by while I avoid writing. Not a sustainable way to build a writing career.

Things I’ve tried to get the writing done with some success:

- Light a scented candle during writing sessions.

- Writing in a room away from my studio.

- Co-working with friends.

- Writing at a coffee shop or library.

- Telling friends I’m committed to writing for a set period, then check in with them after.

- Formal Accountability Groups.

- Leave my desk with a plan for the next day’s writing, or start the next part so it’s easy to jump in to the work.

- Ignore the cooking and cleaning until after the writing is finished. (I like to ignore those anyway. Shhh.)

- Draw my way into the story with scribbly pen drawings.

- I’ve also heard of other authors using Tarot cards to help jumpstart ideas when you’re stuck.

- A friend of mine listens to cafe sounds on YouTube while writing.

- Set a timer. 20 minute segments works well.

- Writing by hand in a notebook away from devices.

Last year, I started co-working with local Kidlit friends. We work in a library or coffee shop so the ‘carrot’ is seeing friends and fancy coffee and snacks. I don’t doomscroll or watch TV due to peer pressure. It works really well. I can quiet my mind, write and enjoy the process! So far, that’s what’s working best for me.

I hope some of these hacks help you with your writing. Let me know if you have any others!

![]() Laura Zarrin has illustrated over 30 books for children including board books, picture books, and chapter books, Highlights Hidden Pictures, and various educational projects. She’s the illustrator of the Wallace and Grace Series by Heather Alexander and the Katie Woo’s Neighborhood series by Fran Manushkin. She’s currently writing and submitting her own stories. Laura is happiest writing and illustrating characters with subtle and not so subtle humor, bonus points for slapstick comedy.

Laura Zarrin has illustrated over 30 books for children including board books, picture books, and chapter books, Highlights Hidden Pictures, and various educational projects. She’s the illustrator of the Wallace and Grace Series by Heather Alexander and the Katie Woo’s Neighborhood series by Fran Manushkin. She’s currently writing and submitting her own stories. Laura is happiest writing and illustrating characters with subtle and not so subtle humor, bonus points for slapstick comedy.

Visit her at LauraZarrin.com or on Instagram @LauraZarrin and Bluesky @LauraZarrin.